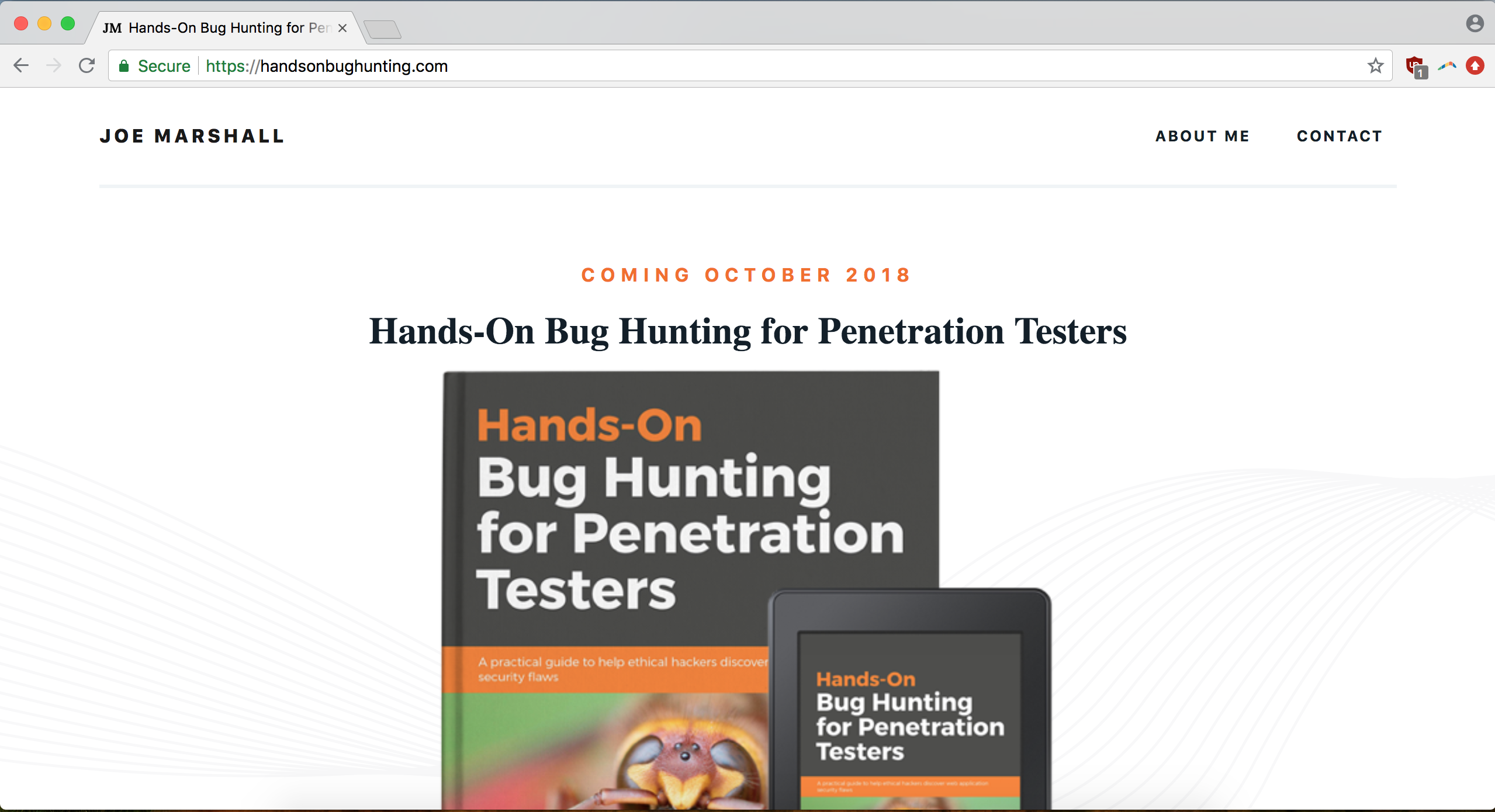

When I was setting out to revamp my personal blog and create a new site for my book, I had a couple of considerations in mind. I wanted both sites to be highly-available (I don’t get much traffic, but also don’t want a hug of death), simple (with as few moving parts as possible), and easy-to-update and generally extend.

All of that led me to a static workflow.

Settling on (but not for) Static

I love static sites. They’re a zen koan in a universe of epics: As large as they need to be (and no larger). Leaning into static sites means that your application is easy to reason about, since it’s just HTML or a simple template generator. And it’s also easy to deploy and host - even just rsync-ing a folder to an nginx server could do for a basic setup.

For the blog, where I would obviously need some level of page generation and templating, I decided to go with Hugo, which used the handlebars-style templating language I’m familiar with, and could generate pages searingly quick, backed up by a simple directory format and a good stable of themes.

For the book site, I only wanted a few pages, why not keep it markup and remove the need for any server-side language or environment dependencies? I had a design friend provide me with the markup and stylesheets.

In the past, I’ve used static site generator workflows where I generated the public directory through my own machine and push it to an S3 bucket wired to a custom domain. I would add whatever post-processing I needed within a build script I kicked off remotely after finishing my blog/update.

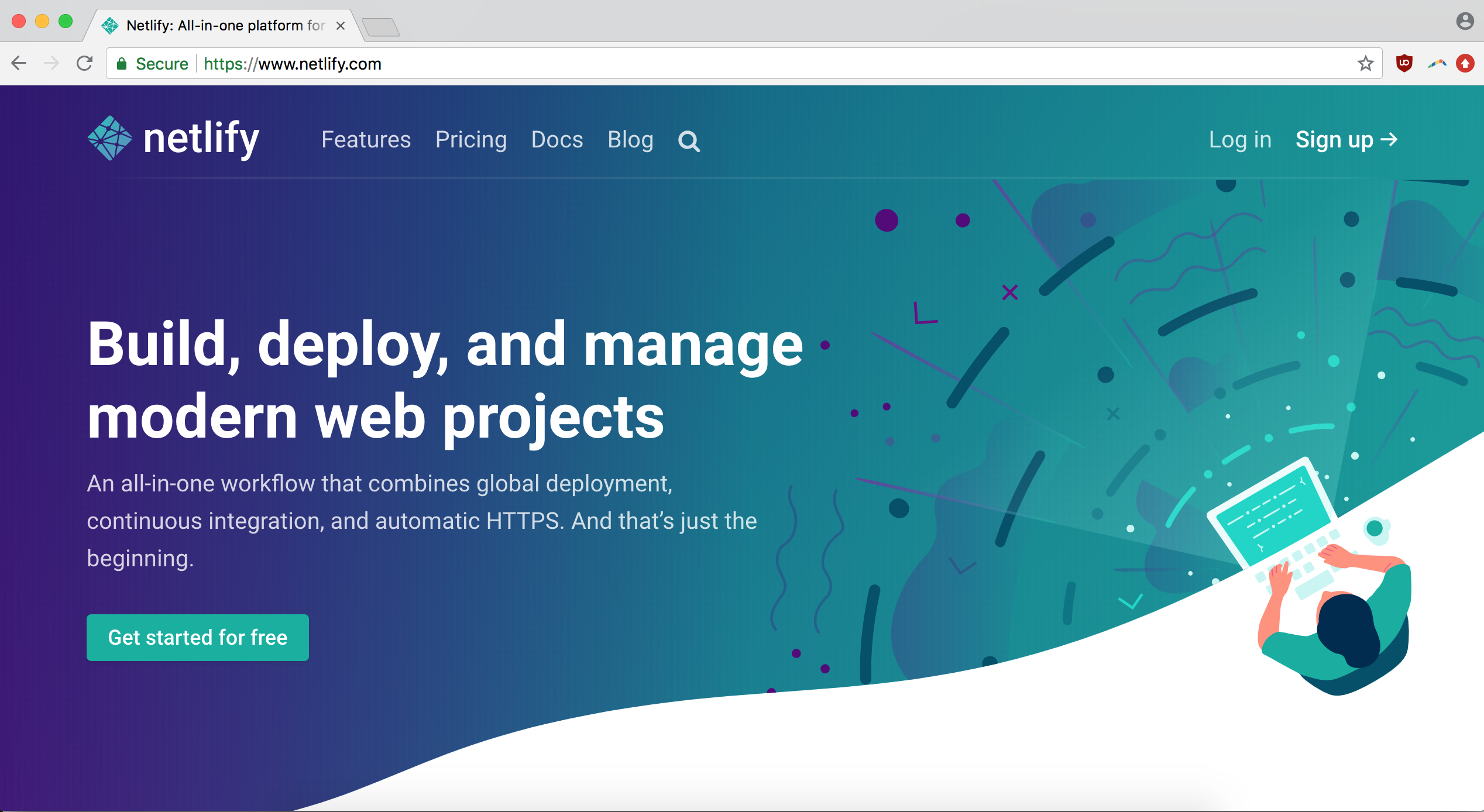

The nice thing about Netlify is how easily you get full continuous deployment right off-the-shelf. Netlify is able to hook into a git repo and then apply your build process to its contents on different branch pushes (there’s one where you just use master, but you can also have split A/B deployments based on named branches) and of course they provide a Hugo template for a quick start.

So for my personal blog (this site), I could give Netlify permissions to access my Bitbucket account (free private repos), then when I pushed to that repo’s master branch, Netlify would generate my public Hugo build, apply post-processing concatenation, minification, and compression, inject my analytics script, and then push the site to their global CDN (free hosting).

I also quickly added a Mailchimp sign-up form (free newsletters) so that I could stay in touch with people who want blog and book-related updates, and connected the Netlify site to a custom domain, the sadly no-free-lunch part of the property - the domain, not the custom domain connection, which is a nice freebie, but the registrar itself.

At this point the stack looks like:

- HTML/CSS/JS

- Hugo

- Netlify

- Mailchimp

- Bitbucket

Implementing the book site is essentially the same process, with one fewer step. Since I’m just using plain ‘ol HTML, I don’t need any sort of build process, just for Netlify to copy the contents of my Bitbucket repo and push it to its CDN. After getting the contents of the markup and CSS from my designer, I can push it up directly, setting up the deploy process to inject an analytics script on each page.

Some Extra Automation

After setting up the sites, I also realized I wanted some basic automation to help with marketing. I don’t want to create a bot to spam Twitter or Linkedin or (Heaven save us!) Hacker News. Those communities have their own issues with programmatic interaction. But. I could create automation to directly replace an action I would normally take manually anyway - at a predictable time. I realized that I could automate posting that I had published a new blog - a regular piece of content - without having to actually login and post the link in each service.

You can find a screenshot-ed walkthrough on inboundmarketing.com but it’s as simple as signing up for Zapier and then having it publish an update to your social networks whenever it detects a new entry in your blog’s RSS field. Since our Hugo theme generates an RSS feed automatically, that option is readily available.

Ah, but we still need the ability to receive email! Both sites have the ability to accept newsletter signups for people interested in receiving updates, but I should also have an email tied to the (for example) book site, so that I can field press and speaking inquiries, address bugs, and other issues under a separate handle without exposing my personal address.

For that there’s Mailgun! After setting up my handsonbughunting.com domain, it’s just a matter of adding a couple of generated records. Then I set an input rule for incoming mail telling Mailgun to intercept messages to contact@handsonbughunting.com and redirect them to my personal email.

Let’s add Google Analytics as our primary analytics solution and this is now our new tally for my personal blog / book site / burgeoning empire stack:

- HTML/CSS/JS

- Google Analytics

- Hugo

- Netlify

- Mailchimp

- Bitbucket

- Zapier

- Mailgun

Possible Limitations and Extensions

I do have some extra functionality beyond the CDN that I’m using Netlify for: Their Forms integration allows me to build a usable form within the deploy process simply by including a netlify attribute in the form element’s HTML tag. This only allows me to accept 100 submissions before it kicks up a pay tier, but if I need to I can always use a drop-in widget (like Type Forms) as a replacement solution. That said, in this case I’d probably just pay for the service.

There’s more than a few ways we could keep extending this (for free): We could add more notifications (via email, Slack, or SMS) tied to important user actions through Zapier; we could back up the data to a cloud file service like Google Sheets (also through Zapier), we could implement any number of locally-hosted scripts through our various services’ webhooks and public APIs.

But this is good for our MVP.

Thoughts on Free vs “Free”

When I set out to design the deploy pipelines and general form of these sites, I didn’t have “totally free” as a priority - I intended to pay $5-$10/month for hosting as I have for previous small projects.

But so much of the free stack is also the cloud-scalable, super-capable stack. Amazon’s Dynamo DB and Lambda, Azure’s Functions and a bunch of other great cloud services are all free because they’re designed to allow developers to play with and build toy apps inside them, validating them for larger, future workloads that will turn a profit for the cloud provider. So in the case of a lot of the free serverless pieces, they’re not only free, but can also scale with your application usage while still being cost-effective, because they’re designed with much more intense production requirements in mind. There are also some services that are so designed for small business and individual developers, that they have a free tier because their clientele couldn’t afford anything else for their trial run.

Of course there are also scummy-free applications that rely on data harvesting, information brokerage, and serving low-quality ads - or just imposing heavy branding / attribution requirements (“keep it for free on your ourservice.com/yoursite domain,” etc). Free services at their worst epiotomize the old truism that “if you don’t have a place at the table, you’re on the menu.” If you use a great service and don’t have to pay, it may be because you’re the product. In some cases, like Gmail, that type of behavior is accepted within certain bounds. But it’s not always a clear trade-off.

But in this case, the universe has aligned to provide us with a couple of simple apps that serve as an effortless, frictionless deploy pipeline to a highly-available global CDN - no weird hostname, mandatory banner, or pesky money required.