Introduction

Last year I published my first book with a publisher, Hands on Bug Hunting For Penetration Testers.

Going in, I was determined to set up a workflow that would allow me to:

1) Keep a backup of the book.

2) Allow me to easily track my writing progress.

3) Work on the book offline.

4) Keep my own copy of the book.

What set of tools could possibly control the versioning, backup, access control, and portability of plain text?

I had all the tools in front of me - and had already started using them. I could use a git repo to keep a backup of the book and track changes, using Unix tools like wc, cat, ag (basically a faster grep) and others to accomplish everything I needed to - in a workflow I was already comfortable with.

It was tooling kismet.

Layout

Here’s how the book repo is laid out.

book/

code/

docs/

manuscript/

promotions/

cover.jpg

outline.md

review-notes.md

technical-instructions.md

The directories should be pretty self-explanatory and, as you can tell, deal with more than just the immediate manuscript. promotions lets me keep track of guest blog ideas, content strategy campaigns, and tactics I’m coordinating together with my publisher’s marketing team. code is all my code (surprise!) Although I haven’t found it necessary yet to program a solution for inlining the code snippets, yet (I just copy them over), it could definitely be done.

docs is for research I’m compiling in the course of writing the book, so I can ensure everything is properly cited, and I can pull in the original document for my publisher to inspect if they want to know the source of an idea, statistic, graph, or other quoted resource.

The files are also pretty direct. outline.md is an outline, review-notes.md is a file where I keep my notes on my publishers notes, thinking in text about how to shape the book using their suggested edits. technical-instructions.md is where I’ve kept any extra-textual instructions on setup and troubleshooting, for the technical editor to review, and the cover.jpg is, well, the cover.

The Manuscript

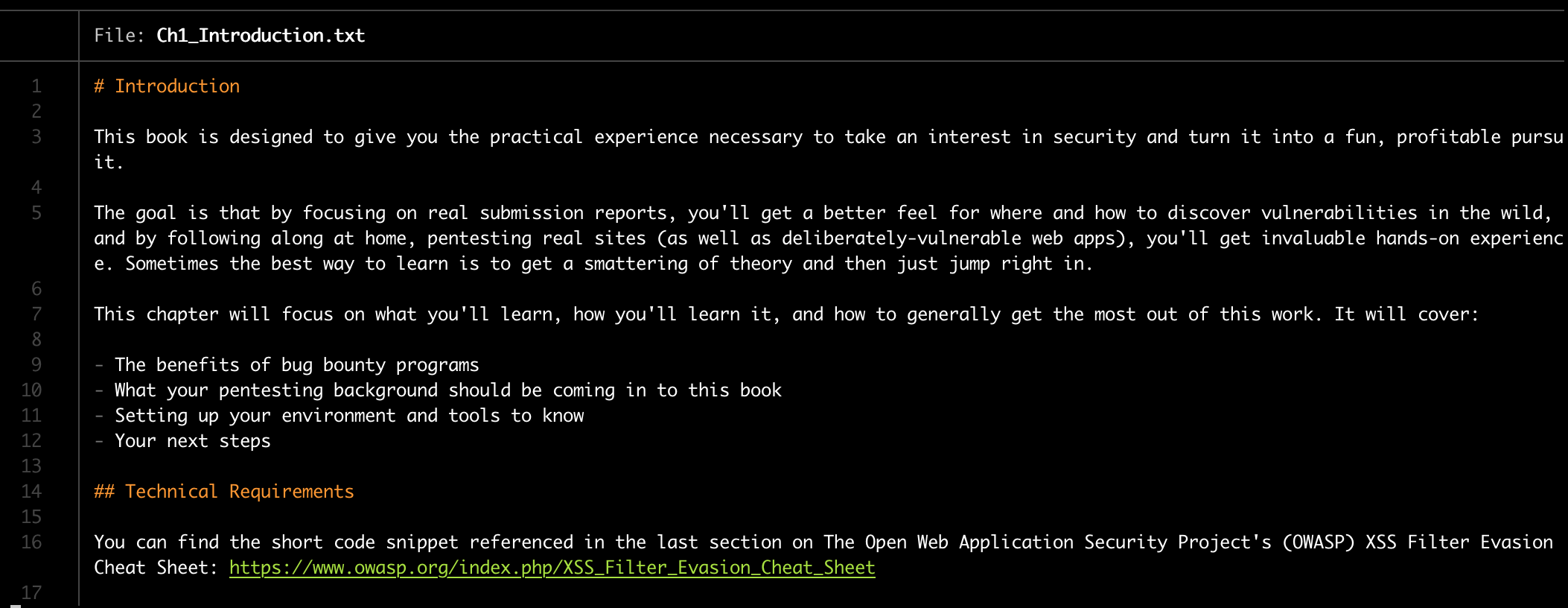

But let’s take a deeper dive into the meatiest part of this setup - the actual manuscript.

book/

code/

docs/

manuscript/

Preface.txt

Assessment.txt

Ch1_Introduction.txt

Ch2_Choosing_Your_Hunting_Ground.txt

Ch3_Preparing_for_an_Engagement.txt

Ch4_Unsanitized_Data_A_Case_Study_in_XSS.txt

Ch5_SQLi_Code_Injection_and_Scanners.txt

Ch6_CSRF_and_Insecure_Session_Authentication.txt

Ch7_XML_External_Entities_XXE.txt

Ch8_Access_Control_and_Security_through_Obscurity.txt

Ch9_Unvalidated_Redirects_and_Social_Engineering.txt

Ch10_Framework_and_Application-Specific_Vulnerabilities.txt

Ch11_Formatting_your_Report.txt

Ch12_Other_Tools.txt

Ch13_Other_(Out-of-Scope)_Vulnerabilities.txt

Ch14_Going_Further.txt

images/

promotions/

cover.jpg

outline.md

review-notes.md

technical-instructions.md

Flat is better than nested, always. Rather than have chapter directories and possibly keeping images together, I went this route so that I could keep this nice at-a-glance view.

You might be noticing though - why use the txt file extension here but not in other files like review-notes.md, where I use the md? That’s because of a simple wrapper I wrote out around wc. I call it txt and keep it symlinked as a command under /usr/local/bin/txt.

#!/bin/sh

total=0

for FILE in `find . -type f -name "*.txt"`

do

wc -w $FILE

words=`wc -w < $FILE | tr -d ' '`

total=$(($total + $words))

done

printf "%'d" $total

echo " words

All this does is add the word count returned by wc and show the total word count of all the .txt files under the path where the command is called, with a file-by-file breakdown As you can see, it only targets .txt files, so using that convention we can keep .md out of the count.

How about images? For that directory I try to use its own naming convention:

arachni-cli-sqli.png

arachni-help.png

arachni-html-report.png

arachni-sqli-timing-attack-part-two.png

arachni-sqli-timing-attack.png

There’s no formal convention of chapter-topic-modifier (next time!) but even just grouping common images under compatible topic buckets everything together in an alphabetically-sorted view, and makes it easier to navigate. And because the images are in the manuscript directory, right alongside the individual chapters, referencing an image in a chapter looks like:

Coincidentally (or not) the layout of my Hugo blog allows me to use this exact syntax and path reference.

Tools

So what do I use to take advantage of this all-markdown, all-the-time workflow? A few things

Sublime Text + MarkdownEditing + MarkdownPreview

Sublime Text has a couple of great plugins for working with Markdown. Together, these two plugins give you syntax highlighting, a better background / text theme, centers the text, and allows you to use a shortcut to preview the document in your browser.

Bat

Do you use bat? You should. A “cat clone with wings,” it provides beautiful syntax highlighting, less, and a bunch of other goodies, while also acting as a direct drop-in for cat.

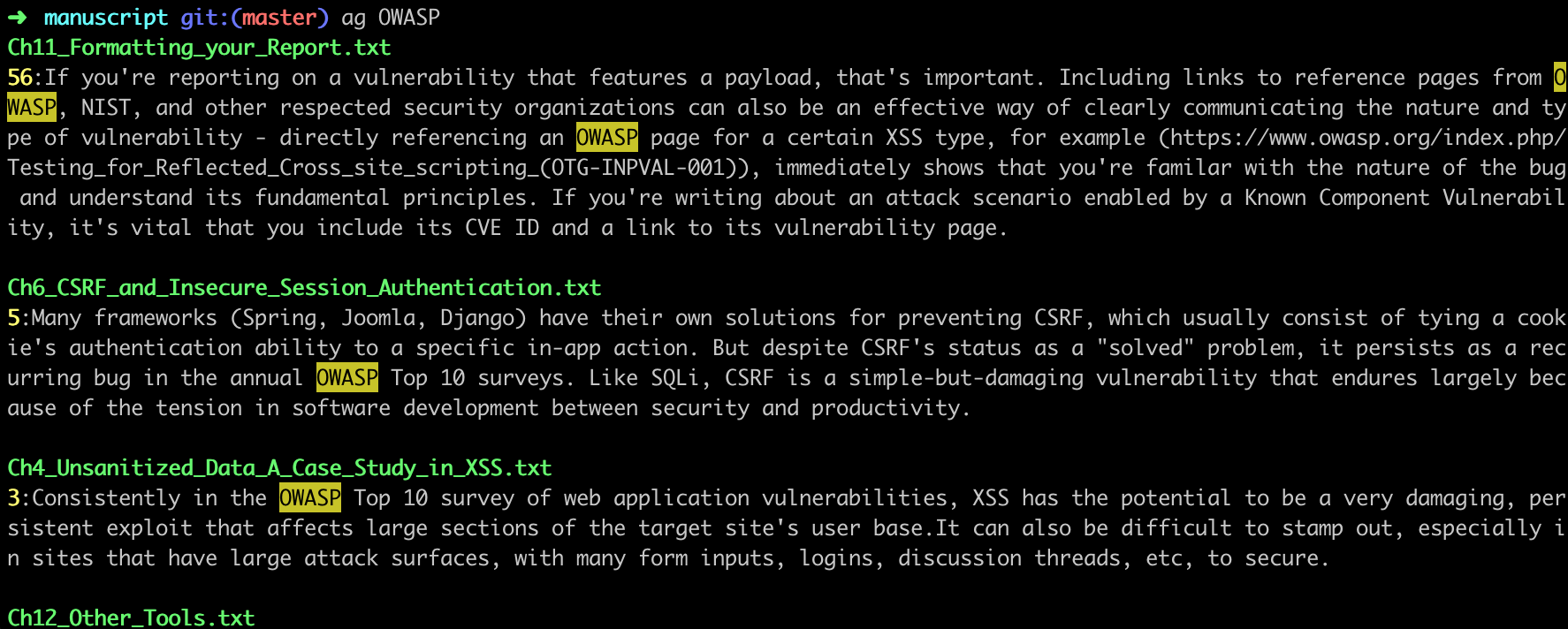

Ag

ag is just a faster grep, basically - and having access to quick, easy, full-text search functionality is key. Being able to easily answer questions like “When have a previously referenced OWASP?” in order to avoid repeating myself, or get a quick refresher on how much background I’d given or what I’d already covered, is great.

Write

I paid for the Write app a few years ago to try it out, and though I’ve moved on to Sublime Text, I keep it for it’s greate translation ability. Using it I can convert a markdown file to a pdf, doc, rtf, or other common format.

Anything, Really

There’s so much more I could incorporate into the workflow that I haven’t already. Maybe I could set it up so that if I didn’t push a commit of a certain size in a certain period to Github, I’d get a Slack reminder - or use my plain text corpus to create a NN that would try to autocomplete my writing in my own voice. The sky’s the limit! Using the plain-text, markdown-first approach opens up the possible ecosystem to include pretty much anything in the Unix mold.

Advantages

Using this workflow I get all the advantages a programmer does with code - a robust version history, a repo back up system (through strategic use of remotes), easy collaboration (add your editor as a github collaborator), and I don’t get locked into any proprietary formats, or rely on some third-party online editor where I fundamentally don’t control what I’m writing.

And I get the portability of markdown! Though my publisher, Packt, requires you to use an online CMS to write books with them, it lacks some of the tooling I need (and has the always-online problem). But because it also uses / supports markdown through a combination markdown/WYSIWYG system, all I have to do is copy and paste each chapter in as I finish it.

Parting Thoughts

The beauty of this system is that you can transpose it onto just about anything. If you write a blog using a static site generator (like I am), then you’re probably already formatting your posts as markdown files under a posts or similar folder.

When all long-form writing projects (documentation, books, blog posts) can use the same system, you get a beautiful convergence of tools that lets you just write, without getting hung up on which particular solution (Word, Google Docs, flat file) fits what particular content.